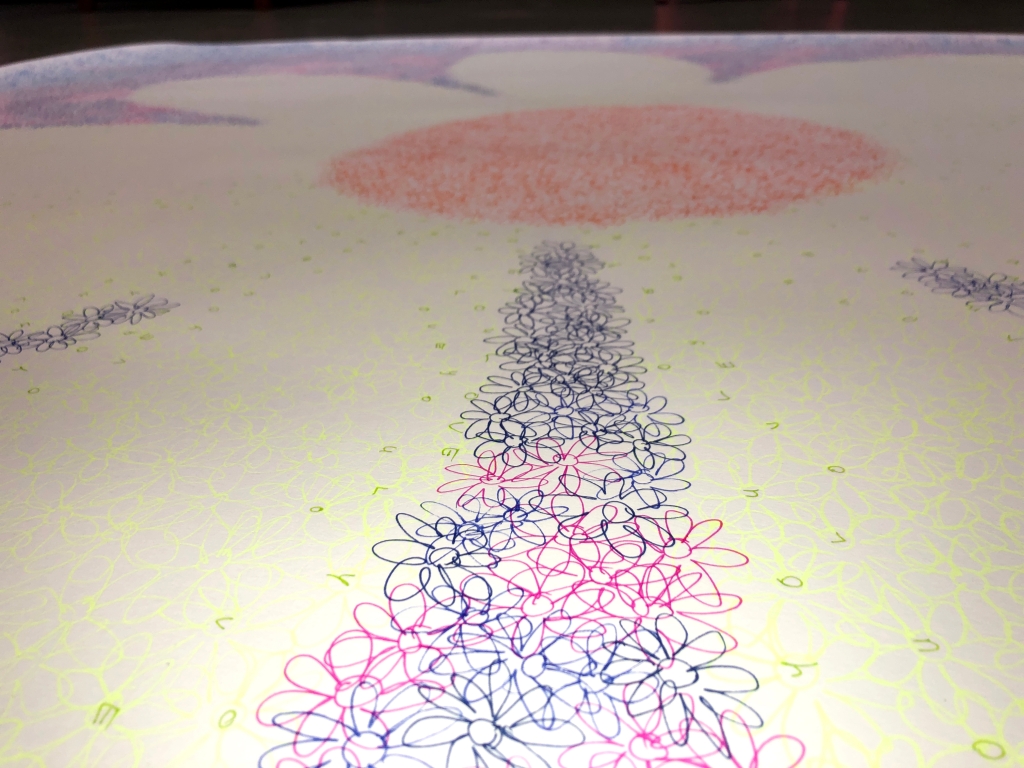

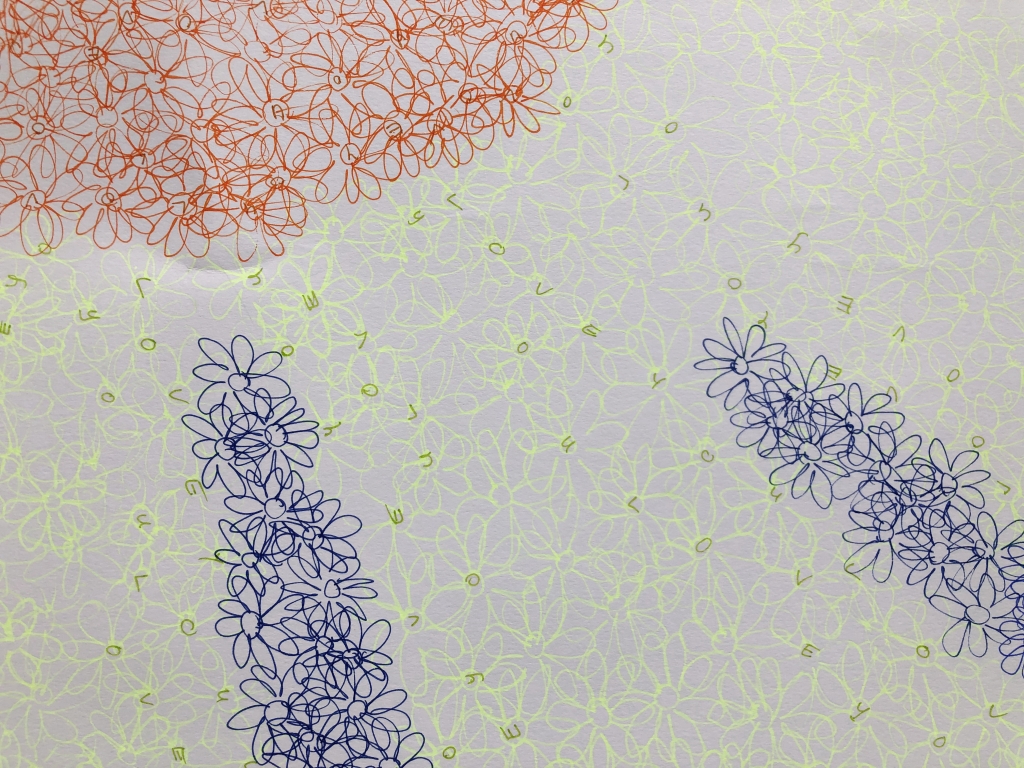

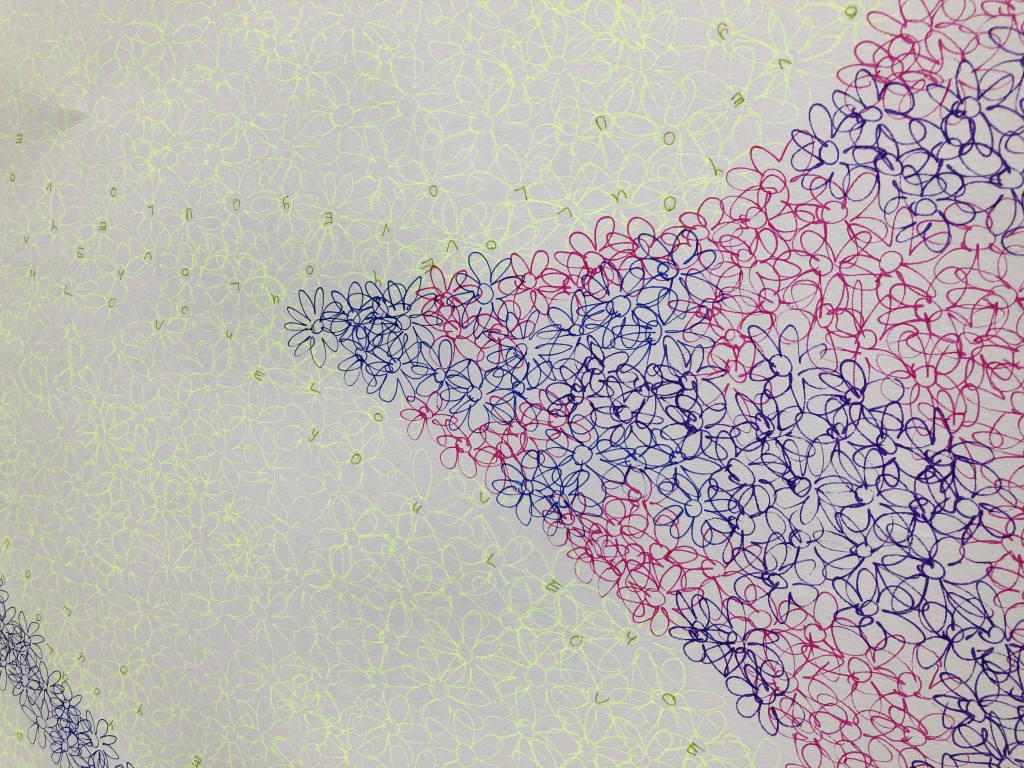

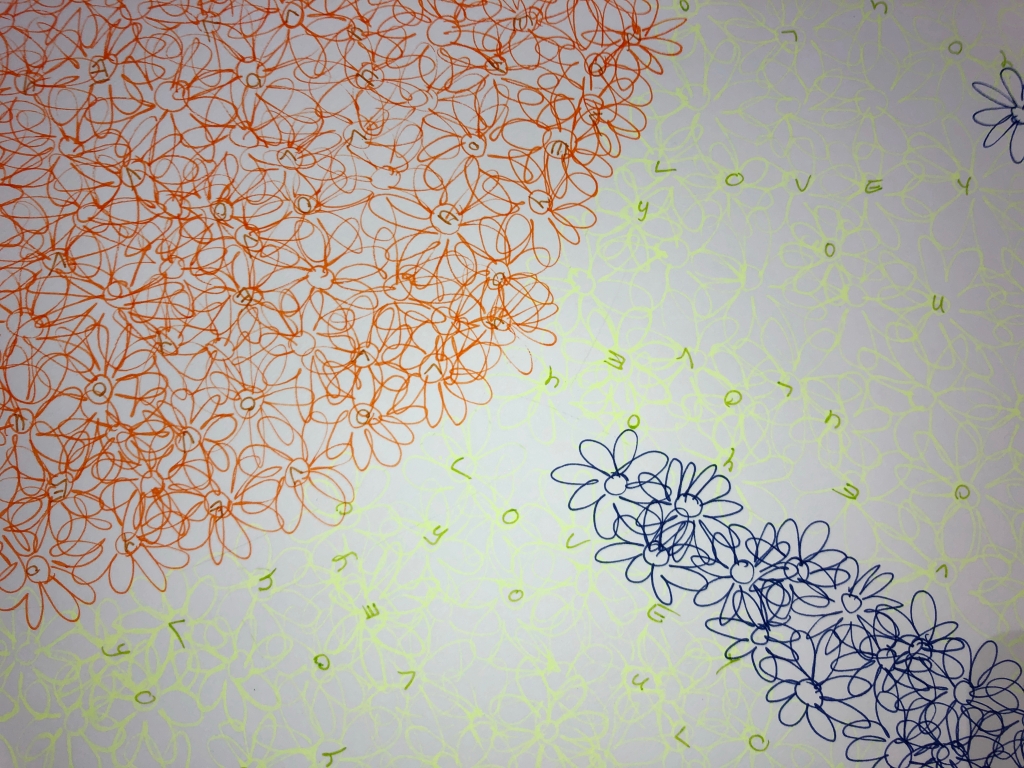

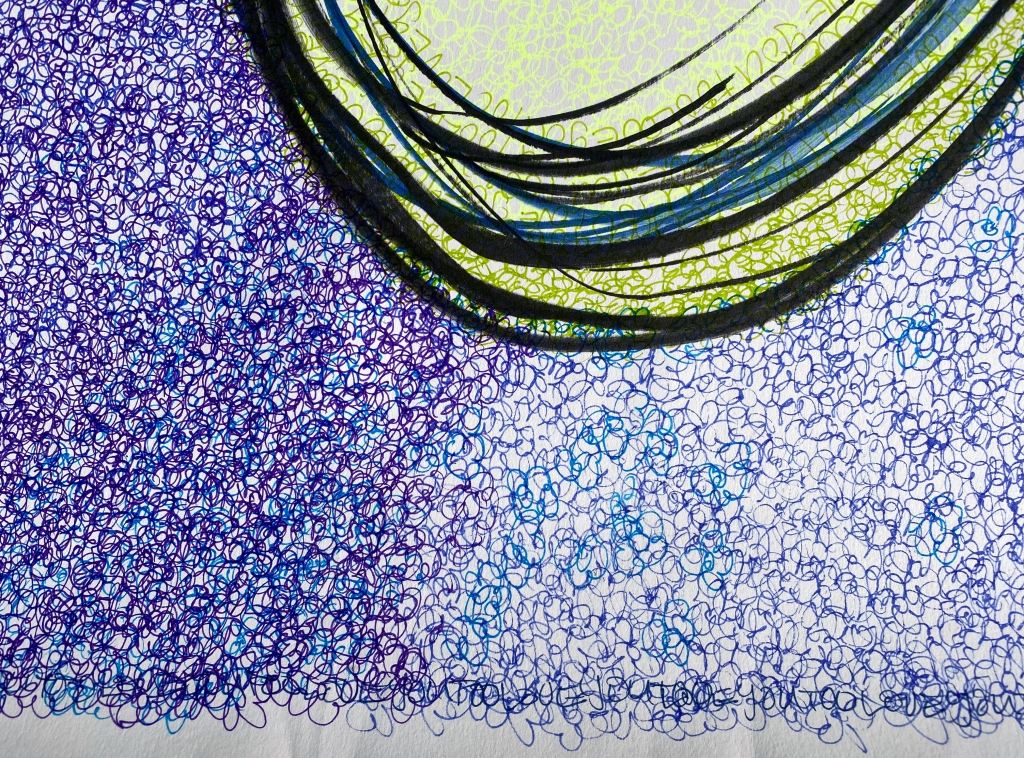

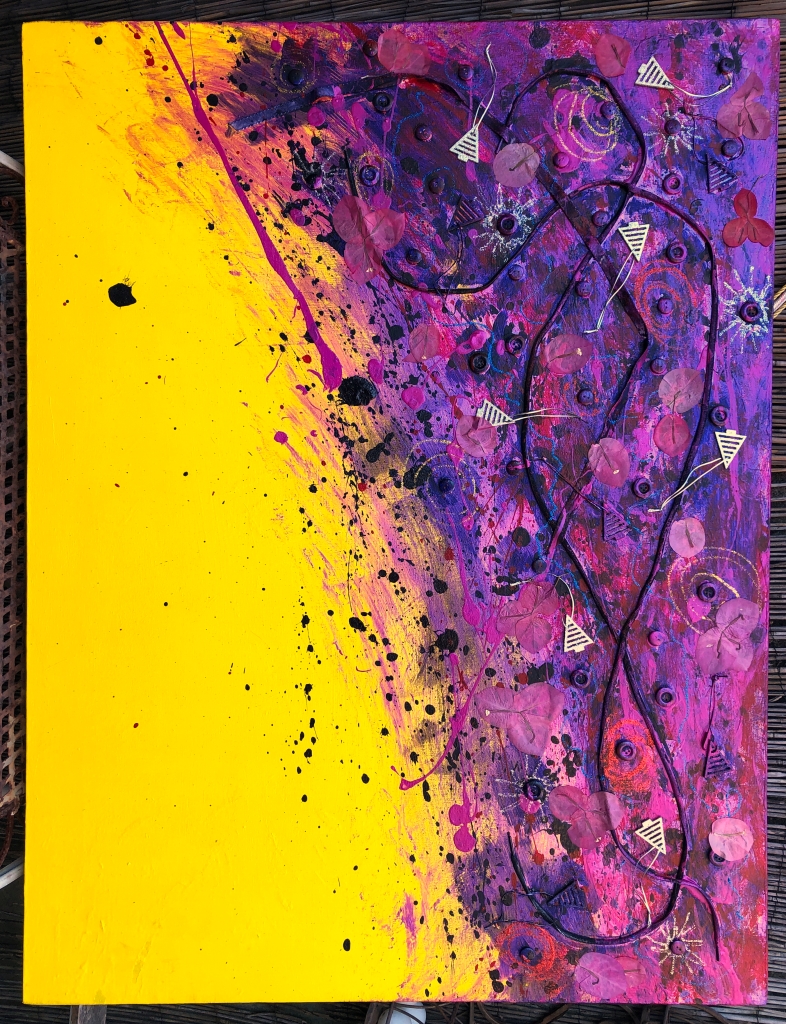

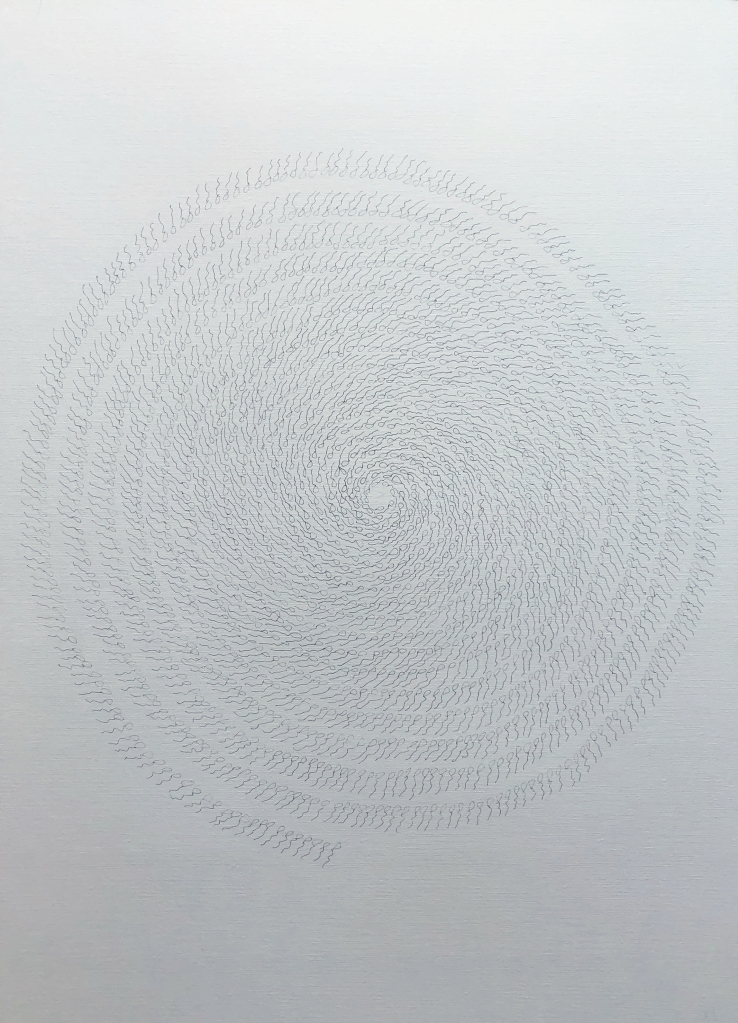

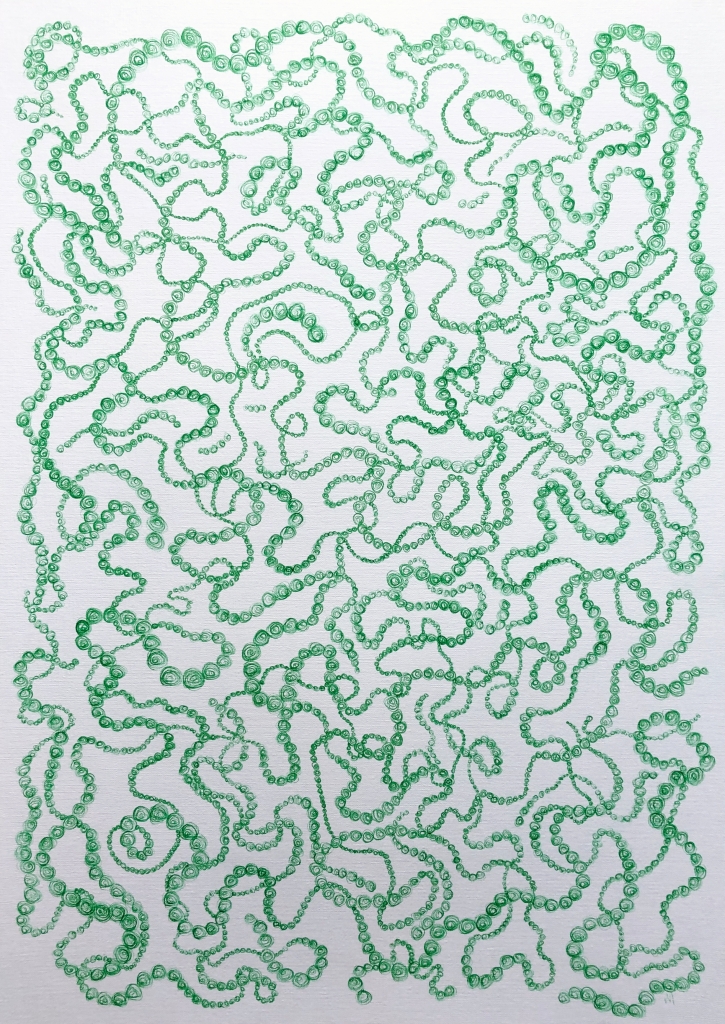

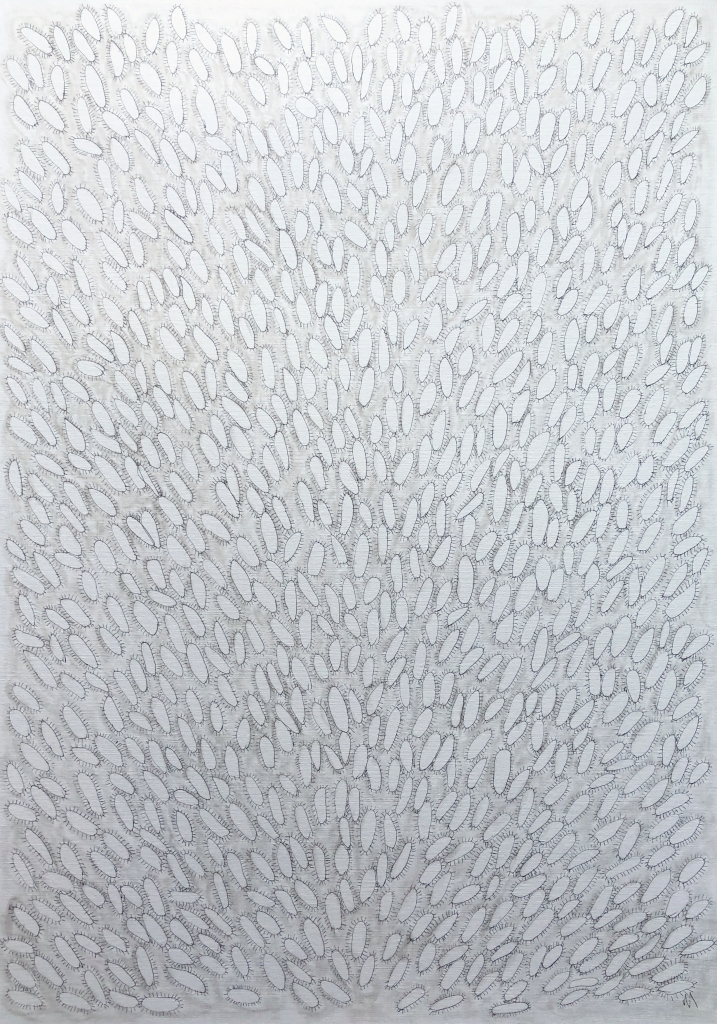

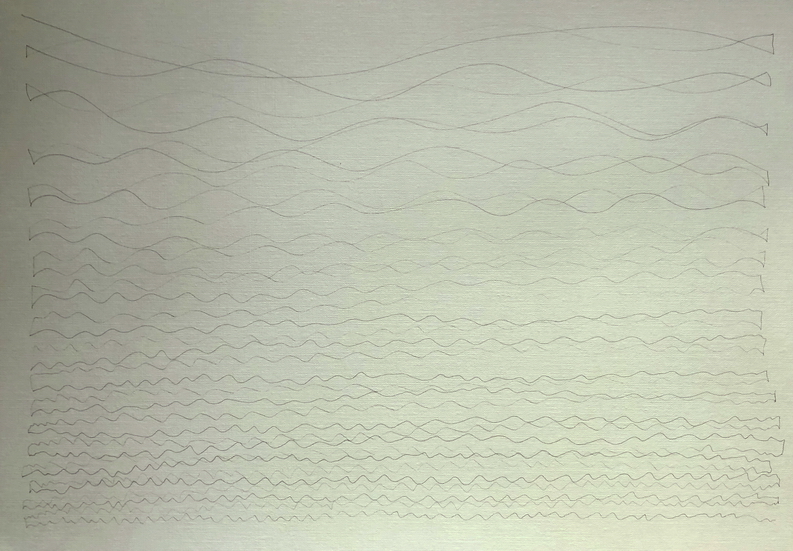

Silueto is a series of interventions marking my existence in the landscape using found materials whose ephemeral nature generates a particular aesthetic. Conceptually, each photograph records the post-presence of the body within the landscape.

That said, let’s talk about Ana Mendieta.

Ana Mendieta was born in Cuba in 1948, but at 13 was sent to the USA to escape political persecution. She earned a Masters in painting at the University of Iowa but quickly expanded her practice in Hans Breder’s new Intermedia course, a performance-led programme challenging students to create art “across and between a plurality of media and distributed and presented in a variety of contexts” (Viso et al., 2004, p. 41).

Intermedia became the first master-level syllabus in the country to introduce art students to an interdisciplinary approach, encouraging them to explore unconventional formats, combinations, principles, and materials. Intermedia students, who came from different areas of studio art (painting, sculpture, photography), performing arts (dance, theatre, music), writing, and film, attempted to integrate aspects of their individual disciplines into the development of more conceptual forms of expression. (Hertzberg, 2004, p. 138)

In an essay I wrote last year – and have cited because not doing so is plagiarism – I explored Mendieta’s sense of place as a brown-skinned, female, Cuban migrant in mid-20th century the USA (Matti, 2019).

Mendieta declared herself “between two cultures” (Brett, 2004, p. 181), a position which infused her work with “alienation and displacement” (Baker, 2016, p. 3). She located her practice specifically in a grant application:

I have been carrying on a dialogue between the landscape and the female body (based on my own silhouette). I believe this to be a direct result of my having been torn away from my homeland during my adolescence. I am overwhelmed by the feeling of having been cast from the womb (nature). My art is the way I re-establish the bonds that tie me to the universe. (Viso et al., 2004, p. 47)

I was not “cast from the womb” because migrating was a free choice for me, but I am definitely between cultures and that drives a need to understand my connection to place: when I’m in Australia, I often reminisce about New Zealand; when I’m in New Zealand, I dream of Australia.

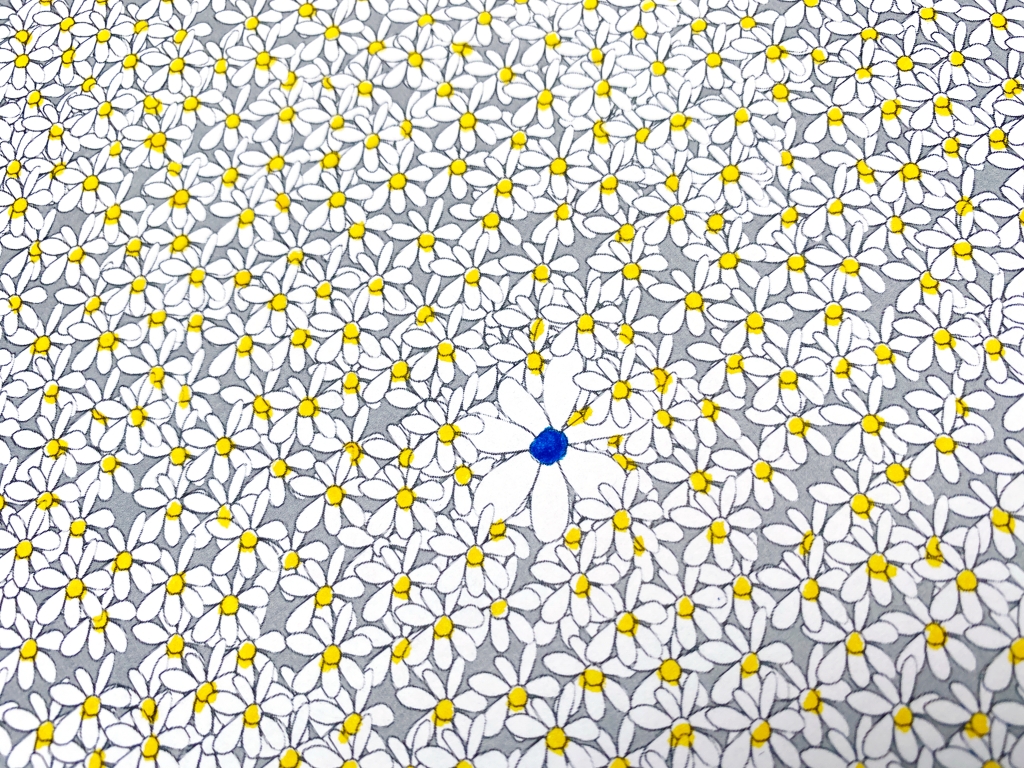

Mendieta’s first Silueta is an “earth-body work” (Viso et al., 2004, p. 22) called Imagen de Yagul. As she lay naked in a pre-Hispanic tomb, covered with white flowers, Breder shot several documentary photographs. She printed just one in order to share the “deliberately ephemeral and temporal (action)” (Sabbatino, 1996, p. 162).

For the artist, each Silueta was “a private act of meditation and dedication” (Iles, 2004, p. 221) combining several art forms: Body, Feminist, Land, and Performance. Body Art is the use of the artist’s body in the artwork, as a material, surface, tool, or technique. Feminist Art is about breaking down the patriarchy so that other voices can be heard. Land Art involves using the Earth as an integral part of the work (i.e. setting, surface, and/or material). Performance Art (not quite the same as performing arts like music and theatre) involves people generating a living artwork which ceases to exist in its original form once they cease performing.

Mendieta took her transdisciplinary nature a step further by including the documentation as part of a larger work “in the time and place of their creation and in the residues and documentation that live afterwards… both the ‘body earthwork and photo’” (Viso et al., 2004, p. 70). This let her explore “the interstices between conceptual, performance, and land art, and how these practices intersect with feminism and the gender and identity debates” (Viso et al., 2004, p. 26).

Her attitude was directly inspired by her studies but also the zeitgeist of the 60s and 70s: traditional art’s rules were melting away under the intense scrutiny of Contemporary Art, which gave itself the freedom to question everything, even the questioning.

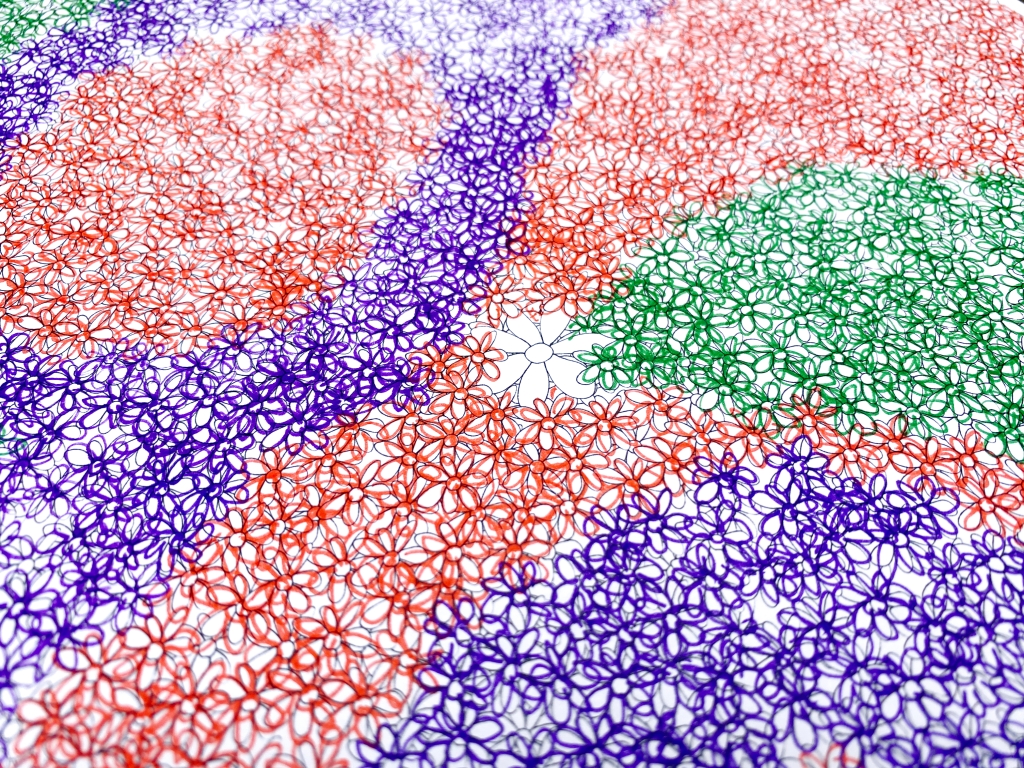

Meanwhile, this post is about my Siluetos, beginning with interventions I performed on a beach in New Zealand. Mendieta’s works are known as Siluetas (Spanish for silhouettes); “Silueto” is a neologism that honours Mendieta as progenitor while changing the feminine suffix to masculine for differentiation. I locate my practice as riffing off her original works, sharing transgression in the social space by acting outside normativity, expressing performativity as an act of meditation and dedication, and promoting environmental awareness.

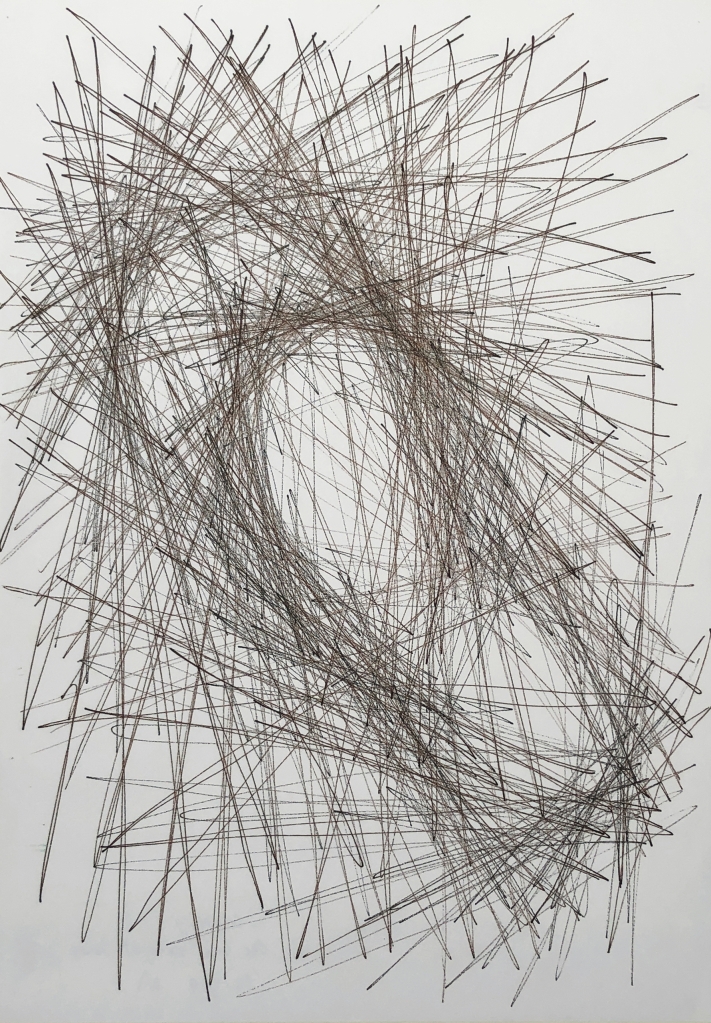

My first intervention was a direct response to one of Mendieta’s: I lay on the sand and drew my outline with seaweed. Then when I stood to document the work I discovered an indentation in the sand, meaning that I’d made more of a mark than I’d intended.

There is a clear relationship between these two works, although I find it fascinating that Mendieta’s looks female while mine looks male.

At this beginning stage, the Siluetos are minimalist because they are deliberately made from just two physical aspects: the landscape and materials found therein.

As these first figures were produced in and of the landscape, I left them to degrade by natural forces. I like the idea that all my effort only alters the environment while I’m there. As soon as I leave, entropy begins erasing my actions. I will eventually bring my own materials, more like Mendieta’s “blood and gunpowder” (Quinn, 2017, p. 148).

After the intervention, I document the trace with my phone camera. Sometimes, this trace is so environmentally congruent that it disappears (later urban interventions are more visible because the location is usually monotonic). The photographs are a vertical “portrait” which fills the frame, followed by a horizontal “landscape” which shows the Silueto in its environment.

Like Mendieta, I prefer to “fuse with the land rather than aggressively mark nature” (Viso et al., 2004, p. 69) and keep these site-specific self-portraits “ephemeral and temporal” (Sabbatino, 1996, p. 162). A mark in the sand (Figure 9) can be quite ephemeral, not to mention well-camouflaged.

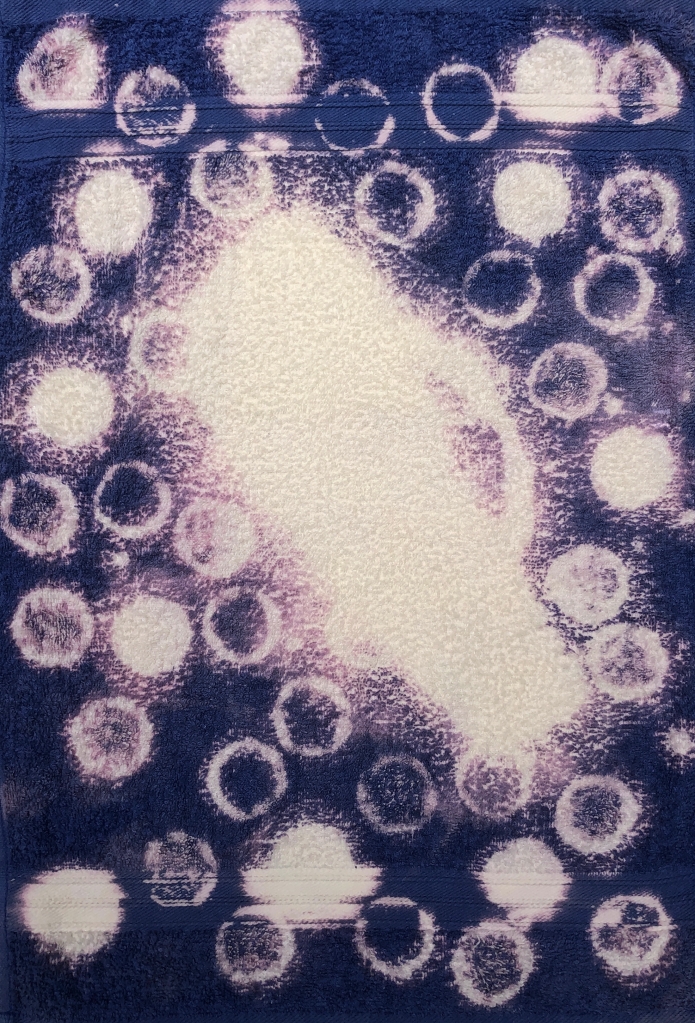

My most transient piece in this location was situated in the tidal zone like Mendieta’s (Figure 10), being erased faster than I could create – let alone document – it.

Mendieta’s guerrilla style is a transgressive political action protesting racism, misogyny, and environmental destruction. When performing a Silueta, she often took friends along to document while watching for the authorities. There were no authority figures for the Nuhiti Interventions but this will change as I explore different locations.

Another way we differ is in the Cuban Santería religion. Mendieta was exposed to it in her childhood and made it a focus of her work. I was raised as more of a compassionate free-thinker so that is the comparative focus of my work: I don’t set out to create suffering but I don’t limit what I can imagine either.

The Ochún Silueta (Figure 13) symbolises the Santería deity of rivers who correlates to La Virgen de Caridad del Cobre, the patron virgin of Cuba and all who brave dangerous waters. Performed across the Florida Strait from her homeland, it is a poignant declaration of here and there, union and separation, earth and water, and the impossibility of being in two places at the same time (León, 2019, paras. 4-5).

Mendieta focused what she felt important, hybridising conventional practices with unconventional ones. For Olga Viso, this was a defining characteristic:

(Her) unrelenting exploration and ultimate abnegation of all forms of boundaries…, her process of making is another aspect of her “between” position. The artist sets in motion a process but does not control its outcome. She allows nature to take its course. She is acted on as much as she acts. (2004, pp. 134-185).

Meanwhile, each of my performative actions is an intimate product of agency, altering the social space and embedding the work into its cultural context: male, masculine, migrant, natural, rural, urban, performative, meditational, physical, metaphysical, entertaining, artistic, conceptual, photographic, sculptural, and transgressive.

Bibliography

Baker, E. A. (2016). To Be Magic: The Art Of Ana Mendieta Through an Ecofeminist Lens.

Brett, G. (2004). One Energy. In O. M. Viso (Ed.), Ana Mendieta: earth body: sculpture and performance, 1972-1985 (pp. 181-204). Washington, DC: Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, in association with Hatje Cantz.

Hertzberg, J. P. (2004). Ana Mendieta’s Iowa Years: 1970-1980. In O. M. Viso (Ed.), Ana Mendieta: earth body: sculpture and performance, 1972-1985 (pp. 137-180). Washington, DC: Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, in association with Hatje Cantz.

Iles, C. (2004). Subtle Bodies: The Invisible Films of Ana Mendieta. In O. M. Viso (Ed.), Ana Mendieta: earth body: sculpture and performance, 1972-1985 (pp. 205-223). Washington, DC: Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, in association with Hatje Cantz.

León, C. A. (2019). Trace Alignment: Object Relations after Ana Mendieta. Retrieved from https://post45.org/2019/12/trace-alignment-object-relations-after-ana-mendieta/

Matti. (2019). Carl & Ana: The Breakdown of Artistic Disciplinary Boundaries Since 1960. (BFA). University of New South Wales, Sydney.

Quinn, B. (2017). Broad Strokes: 15 Women Who Made Art and Made History (in That Order). San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books.

Sabbatino, M. (1996). Ana Mendieta: Identity and the Silueta Series. In G. Moure (Ed.), Ana Mendieta (pp. 135-166). Barcelona, Spain; Galicia, Spain: Ediciones Polígrafa; Centro Galego de Arte Contemoránea.

Viso, O. M., Mendieta, A., Herzberg, J. P., Iles, C., Brett, G., Roulet, L., . . . Miami Art Museum. (2004). Ana Mendieta: earth body: sculpture and performance, 1972-1985 (O. M. Viso Ed.). Washington, DC: Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, in association with Hatje Cantz.

You must be logged in to post a comment.